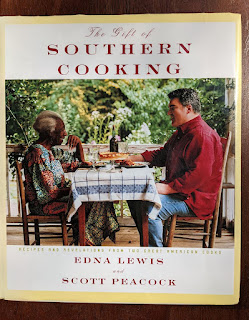

Jesse's Cookbook Reviews: The Gift of Southern Cooking, by Edna Lewis and Scott Peacock

Y'all remember the Culinary Mt. Rushmore episode, right? When Jesse delivered his tirade about the big shapers of American cuisine? (If you don't recall, it was Julia Child, Alice Waters, Thomas Keller, and Dave Chang. Here's a link to the companion, if you can't be bothered. And then, on the next episode, John Huff emailed us, and asked us where we were at on Edna Lewis? And I referred to her book A Gift of Southern Cooking over, and over, and over... But here's the thing. At the time, I hadn't read it. I got the titles of her books crossed up in my head. The one of hers I had read was In Pursuit of Flavor. I mentioned this in the errata, but out of sheer embarrassment, I went out and bought a copy of the former book straightaway.

See, as much as I value Lewis's contribution to American cuisine (being one of the first African-American celebrity chefs, as well as one of southern cuisine's early ambassadors in the north), In Pursuit just wasn't that good a book. It was plagued by a lot of the standard problems that are common in cookbooks from decades ago, or by very old cooks who don't have formal education: imprecise measurements, a fair number of wive's tales dispersed among the culinary wisdom, bizarrely dogmatic stances on odd topics (I'm reminded of Elizabeth David's conviction that wrapping something in plastic wrap, rather than brown paper, caused it to warm and spoil)... I valued the insight, the wisdom, and the inspiration, but the actual recipes, less so. It was a book I'd recommend to a seasoned home cook, or a student of southern cuisine, but be cautious about recommending to a beginner., this volume dials a lot of those problems back a good bit. Sometimes, an old-timer just needs a good writing partner to be really effective, and Ms. Lewis found hers in Scott Peacock, a formally trained chef whose big claim to fame was being the chef of the Georgia governor's mansion for a while. He's also a pretty good writer, better than Lewis, and is far more effective at coherently telling a cook what they should be doing. However, he defers to respect, always, so it never sounds like he's talking over her. It's clear that they have a long-standing personal and professional relationship, so he sounds less like her editor, and more like her advocate. They make a good team, like Julia Child and Jacques Pepin, or Thomas Keller and Michael Ruhlman.

The Concept: This book seems to be striving to be a rather comprehensive work on southern cuisine, or, to be more specific, the cuisine of the southeastern US, from a primarily WASP/African-American perspective. They don't get into Creole cooking, of Floribbean or Texan, and that's a good thing, I think. Sometimes southern cookbooks can get bogged down trying to do everything. This book digs deep into the cuisines of Georgia, Virginia, the Carolinas, Alabama, and Mississippi, along with the eastern parts of Tennessee and Kentucky. It makes no effort to be scholarly (for that, check out Bill Neal's Southern Cooking, from University of North Carolina Press), but it does contain some historical information. However, it's shot through with a lot of personal, reflective content as well, so you are what you are reading is as much a portrait of the authors' southern food experience as a portrait of the cuisine itself.

The Specifics: 330 pages, and something like 330 recipes, divided into chapters on condiments/drinks, soups, salads, fish/poultry/meat, vegetables/sides, 'supper dishes', breads, desserts, cakes/cookies, and frozen desserts. This seems like a lot of content, but sometimes the recipes are super elemental or simple. For instance, there are 2 different chicken stocks, recipes for rice, iced tea, there's a lot of padding. On the other hand, that padding actually makes this a pretty decent prospect for a beginner, someone who wants to get 1 cookbook to be their go-to. Of special interest is the 'supper dishes' chapter. Exactly what this means isn't clearly communicated. It defines 'supper' as the lighter evening meal after a big Saturday or Sunday lunch, and talks about dishes that are driven by leftovers, but that's pretty vague, and not all that well-adhered-to. (I've always found distinction between 'dinner' and 'supper' to be pretty pretentious. In my upbringing, 'supper' was a southern/rural term, and 'dinner' was a northern/city/town term, and that's kinda that. Anything past that feels like sentimental posturing.) I feel like, more than anything, this chapter served as a lazy catch-all to handle dishes that could be entrees, except they had defined their entree chapter by animal protein, and they were trying to come up with a rustic/sentimental way to brand it. Oh well, most southern cookbooks fall prey to at least one such indulgent flight of fancy. I won't dock them for that.

What's Good: Well, firstly, a lot of the recipes are really solid (more on this later). Also, as I said before, this book makes an effort to be comprehensive, at least as far as southern cuisine goes. They have recipes for the basic fundamentals, along with southern classics and church picnic nostalgia dishes. Assuming one had the requisite culinary chops to get past the technical issues (see 'what stinks' for details), this would be an ok one-stop shop for a southern home-cook to use as their home-base recipe book. Also, I have to say how well the team of Lewis and Peacock seem to work together. Having the young white man speak for the elderly black woman might sound like a pretty bad look, but he carries his responsibility off with total respect and deference. He doesn't seem like he's dominating the narrative, he just seems like he's shouldering the workload, which is fair enough since his writing partner was in her mid-to-late 80's when they were writing this.

And, there are some fantastic little culinary tricks and cultural titbits in here. For instance, they recommend putting the vegetables for chow-chow through a meat grinder. What a great idea! You save hours of chopping, but it won't pulverize them the way a food processor could. I never would have thought about goosing up lemonade with a sprig of mint and a pinch of salt, but it sounds delicious! This is one of the first American cookbooks I've seen that presents a strong, comprehensive case for the brining of white meat and poultry. The idea of making a chess pie with brown sugar instead of white is alluring, and novel. It never occurred to me that 'johnny cake' could be a corruption of 'journey cake,' but the little fried cornbreads really do make sense as a travel snack. And I can thank this book for finally explaining to me why lowcountry boil is sometimes called Frogmore stew. (Spoiler alert: it's named after Frogmore plantation, which is located on St. Helena Island near Beaufort.)

What Stinks: Well, this book only really has 1 major issue, but it has it over, and over, and over. This book often makes authoritative statements on cuisine, or recommendations in recipes, that don't bear out when scrutinized or tested. It's odd. Now, out of a writer of Lewis's age, I'd expect this. Technical precision in recipes is a relatively recent invention, and precision tools of measurement (digital scales, probe thermometers, even measuring cups graduated in mLs) were rare until the last 20 years or so. However, this book came out within the last 20 years, and some of the technical claims made are dubious, to say the least. On top of that, there were many claims that, while not testable, were oddly dogmatic, and didn't really stand up to modern scrutiny.

A short list of claims/instructions I took issue with:

-Dry thyme is preferable to fresh thyme. WHAT. This is unorthodox to the point of being heretical. What recipe book calls for fresh chervil, and then specifies dried thyme.

-Using kosher salt in a mayonnaise can cause that mayonnaise to break. Huh, I'd better go back and tell that to the 10,000 mayonnaises I made during my professional career.

-Make a mixed pea soup, but cook all the peas together. Well that goes against every kind of conventional wisdom. What do you do when one type is perfectly cooked, and the others are still sandy?

-Always wash greens in salt water. Why? I've never heard that. That doesn't mean it's necessarily wrong, but you'd think that if it were all that hot an idea, it'd be repeated anywhere else, ever.

-When cooking shad, get the fishmonger to remove the bones. HA! Chance would be a fine thing. You ask my fishmonger to bone a shad, he'll tell you to go bone yourself. It's almost impossible!

-They give equal brine and cook times for quail (average size: 3.5-5 oz.) and a squab (10-14 oz.). That simply cannot be right.

-Running mushrooms under water will 'spoil their flavor.' No, it won't. It will water-log them. If I tell you that it's a good idea to grease your cake pan, because it will appease evil spirits, I have given you good advice, but still not given you any knowledge.

-But the biggest doozie of them all, for my money, is that commercial baking powder contributes to a chemically taste in baked goods. They advocate for mixing your own baking soda and cream of tartar. Note, this creates single acting baking powder, and it doesn't sub 1 for 1 with commercial double-acting baking powder in recipes, so if you bake out of this book, you have to make your own baking powder. Which is fine, it's not difficult, but man, is it annoying. I have never had an issue with commercial baking powder. This really feels like an opinion Ms. Lewis formed 50 years ago, and hasn't tested recently.

But wait!: Aren't you arrogant, Jesse, claiming you know so much more than these published authors, when you are little more than a two-bit blogger and podcaster! Well, yeah, but I back it up. Here is a link to a blog post where I address head-on the question of how one can know, really know, when a cookbook is full of next-level tricks that never occurred to you, and when you need to trust your instincts, and ignore stuff that seems suspect. Long story short, if I have a book I suspect of technical squishiness, I try a recipe that looks particularly suspect. Sometimes, the book will pull an Alain Passard, and be surprisingly innovative, and sometimes it will... not, and I know I can ignore anything that looks too fishy to work. Scott Peacock's chicken stock method failed three ways. 1, it used a size of chicken next to impossible to attain. 2, the method didn't work, the chicken stayed slightly raw in places. And, 3, it yielded an absolutely terrible chicken stock. That recipe was my litmus test. The canary in the coal mine was stone dead by the time I was done. Not a huge issue, but it's important to know when a cookbook has some inbuilt flaws, and that's why I won't be recommending this book to beginners.

Oh, and one more issue: This book also failed to give safety warnings in a couple of recipes where I really feel they are necessary. If a cookbook has recipes for iced tea and rice, and pancakes, one can assume they are appealing to the beginner. Well, if that's the case, then certain recipes absolutely need safety warnings. For instance, in the recipe for pan-fried softshell crab, there is nothing about using a splatter screen, or the dangers of popping grease, a hazard to which anyone that's ever pan-fried a softie can attest. Also, in the recipe for peanut brittle, there's no warning whatsoever on how dangerous sugar is when it's cooked to caramel. Not one word. That's frankly irresponsible. If a rookie cook sent themselves, or worse, their child, to the burn unit because of an omitted sentence about safety, that's a hell of a thing.

Recipes Tested (Here's where this book really shines)

Boiled Dressing

Boiled Dressing: I'd often wondered what was going on with boiled dressing. I'd seen it in old cookbooks as a coleslaw dressing, but I'd never seen a contemporary recipe, or seen it used in a restaurant, ever. Well, as it turns out, it's a cream-based, flour-thickened dressing structurally similar to bechamel, but enriched with egg yolks that are stirred into the hot dressing, so they are no longer raw. Apparently, it has, in the days of widespread refrigeration, largely been replaced by mayonnaise, but in the days before everyone having a fridge in their kitchen, this was a relatively shelf-stable choice for a creamy salad dressing. Sharp with dried mustard, it made a surprisingly cook coleslaw with shredded cabbage, carrot, and onion. So happy I got to try this!

Fried Chicken and Tomato Gravy: Okay, first, let's knock out the tomato gravy. It was a nice, creamy gravy, flavored with chunks of canned plum tomato. I first encountered it at John Currence's Big Bad Breakfast, and my redneck friend Chanda was so excited to see it on a restaurant menu, that she actually called her mom. It was delicious. Even more so, because I used fresh thyme, from D's garden, instead of that dried crap. But unfortunately, it was a waste of time, because perfect fried chicken needs no sauce.

That's right, I said perfect fried chicken. It was a hell of a process. 12 hours in brine, then 12 hours in buttermilk, followed by an overnight drying period in the fridge. So we are up to 32-36 hours already, so I hope you like planning ahead. For the frying medium, the book had me adding minced up country ham to lard and toasting it, while adding whole butter, then straining and skimming the whole thing, until I was left with clear, amber, ham-infused-butter-lard, which makes for quite a tasty medium for fried chicken. Now, the book called for a smaller bird, so I had to finish it in the oven. This recipe was not for beginners, but it made some great goddamn fried chicken.

Mashed Turnips: This was a 'simple' side. I put simple in quotes, because the recipe should have been simple, but was so wonky that it was a real trick to get this done. It had you peel and slice the turnips, toss them in melted butter, place them in a baking dish, cover in foil, and bake till they were tender. However, this method didn't work. Maybe if it had specified 'in a single layer,' it would have been fine, but everywhere the turnips were stacked (hard to avoid, when they are sliced), they didn't cook. I ended up having to finish them on the stove top, adding splashes of water, and tending them until they were all cooked through. If the menu had had me cut them into dice, which were less likely to stack, and more likely to allow air through, it would have been fine. If the recipe had had them shingled in a single layer, they'd have been fine. If the recipe had just said goddamn 'cut the turnips into pieces, bake until tender, and mash with butter,' that would have been perfect. Another exercise in going around one's ass to get to one's elbow, because people either can't write a clear recipe,. or because publishers don't test them. They tasted fine, once I actually got it done.

Greens and Cornmeal Dumplings: The first step to this recipe was to make smoked pork stock, for which they called for smoked Boston butt, which I was able to find at Doscher's, Charleston, South Carolina's most colorfully downmarket grocery store. (Their meat department is no joke. You need pig ears, and you don't want to drive all the way out to the Asian store on Rivers, this is your spot.) This yielded a liquid that tasted, for all the world, exactly like hot dog water. However, as luck would have it, hot dog water os a pretty good medium for braising kale (the recipe called for turnip greens, but kale was the closest thing I could find). Once the greens were cooked, I dropped in little spoonfulls of cornbread batter, and poached them till done. They tasted great, and it made a nice starch/veg combo. The dumplings didn't hold together very well, but I am giving them the benefit of the doubt, since the recipe called for fine cornmeal, and I only had coarse. At any rate, if you try this out, don't jostle the pan while the dumplings cook, they are very delicate.

Creamed Butterbeans with Country Ham: This is pretty straightforward. Butterbeans, blanched, and then glazed in cream and butter with country ham and chives. It came out pretty great, but the cream was kind of cloying, and muted the rest of the flavors. If I was going to do it again, I'd just use buerre monte.

Quail Hash: This was pretty great. This was one of those 'suppertime' dishes, meaning it could be produced out of leftovers, as if anyone ever has leftover quail. Diced quail meat, cooked up in a gravy based on chicken stock reinforced with roasted quail bones, rounded out with celery and onion, all served over toast. Ignore the quail airline breast in the photo, that was my contrivance. Honestly, as good as it was, this would have been even better with just a fried egg. This is a really nice breakfast dish, and a great way to repurpose roasted game bird leftovers, especially the leg meat, which can be really gnarly and tough. Chop it up, smother it in gravy, done deal. Nice dish.

Sourdough Pancakes: Now these were awesome. A great pancake recipe, with a yeasted starter lending a ton of flavor and depth. They weren't all that sour. I wonder what leaving the starter for longer than 10-12 hours would do. But no matter, they were excellent pancakes. I'm unlikely to put these into regular rotation since for me, pancakes aren't always premeditated, and sourdough pancakes really have to be premeditated. Note: this recipe made for a thin-and-lacy type of cake, so they aren't as well-suited for fillers like blueberries as some of the fluffier styles.

Biscuits: Well, I had to make these. One of the things this book brought into my life was a blue tub of lard, so cooking with lard has become a thing at my house. I'd always wanted to try lard biscuits, and now I have. How were they? Pretty good! The pork fat yields great flake, and there was a pervasive savoriness in every bite that was welcome, not obtrusive. It wasn't so strong that the biscuits couldn't be used with jam at breakfast, or as a shortcake, or the base for a cobbler. They were, however, just a shade salty. Also, they used Lewis and Peacocks cockamamie homemade baking powder. I wonder how much more lift they'd have had with double acting, but it's not a 1:1 switch-out, so experimentation will be needed.

Country-Style Rhubarb Tart with Rich Custard Sauce: Another case of unnecessary sauce. In this case, the sauce was creme anglaise, pretty straightforward, but made in the oddest way (the yolks were cooked with the milk, and the cream was added after.... again, why??). The sauce added nothing, and basically trampled the following elements:

-The subtle savoriness and complexity of the lard-and-butter pie crust, which may become my number-one pie crust moving forward (and anyone that knows me knows what a BIG FUCKIN' DEAL that is)

-The delicate interplay between the tart rhubarb, sugar, and dusting of nutmeg in the filling

-The understated nuance of cardamom gained by aging sugar cubes in a jar with cardamom pods for 2 weeks, and then crushing the sugarcubes into uneven pieces and sprinkling them all over the crust

All that technique, all that subtlety, all that nuance, all out the window when you spoon a big dollop of vanilla sauce in the middle.

It's frustrating for a recipe with such grace and attention to detail to be so compositionally inelegant.

Still, I say again, that's my new go-to pie crust recipe, sound the claxon, alert Interpol.

The Verdict: A pretty good book, with some pretty glaring issues. I love what they were so diligently trying to do, and if it was perfect, this would be a great book that could serve a beginner home cook for years and years, as they gradually expanded their repertoire. However, the technical issues mean that this book could pack as much frustration as inspiration, so instead, I call it a very useful book for an experienced cook looking to built out his southern library. It has the great benefit of being relatively removed from the personality of the authors (most of the time), and as a result, is more of a compendium, and less of a manifesto. You can get a copy for less than 10 bucks on Amazon right now, and frankly, if this kind of cooking is your thing, there's no good reason not to. I give it a 3.5/5, along with a precision score of 3/5 (average: rookies beware, seasoned cooks, trust your instincts, if it looks wrong, it probably is).

Stay Tuned: Another old southern dinosaur recipe I always wanted to try was tomato aspic, and this book has one, but I reviewed it in the winter. When the Wadmalaw tomatoes come in this year, I'll be trying that one out, alongside some shrimp and sunchoke salad. Look for it when the weather turns warm.

Comments

Post a Comment